We Have Arrived. The Problem Has Changed

Some thoughts on the 2nd anniversary of my win against The Open University

These reflections have been produced with the help of two close friends - you know who are you. They kept me sane in the run up to and aftermath of the tribunal. I asked them about what they thought had changed for the better and worse since my judgment. Their insights form the basis of this blog. I am indebted to them for their friendship as well as their analyzes.

Today, January 22, marks the two-year anniversary of my employment tribunal judgment against the Open University. For me, it marked the turning point of my life. A struggle I had been involved in for nearly five years had come to an end. I had risked everything — my job, my reputation, my financial stability and security, my mental health — to establish three things in a court of law.

First, that it is not transphobic to ask how, when, and where sex might matter more than gender identity in social and political life. Second, that it is unlawful to make vexatious accusations of transphobia against academics pursuing that line of research. Thirdly, it is unlawful for university managers to do nothing about harassment, discrimination, and victimisation on the basis of gender-critical beliefs.

Two years on, these principles are not merely established; they are settled. The Supreme Court decision in For Women Scotland v Scottish Government is decisive. Within the Equality Act 2010, sex means biology. For those naysayers who claim the ruling is confusing or limited, I say: you are wrong. The law is clear. Sex in equality legislation refers to sex. Gender-critical beliefs are protected. Women’s entitlement to single-sex services and spaces is not contingent on discretion or goodwill; it is a matter of law.

It is worth remembering that I was part of that first flush of employment tribunals where women lost their jobs for saying more or less exactly what the Supreme Court said - Maya Forstater, Alison Bailey, Rachel Meade, Lizzy Pitts, Roz Adams — and myself. We were discriminated and/or lost our jobs for stating that sex is biological and not to be confused with gender identity, for pointing out that men who identify as women have not, and cannot change sex, and for questioning Stonewall’s diktats on the matter.

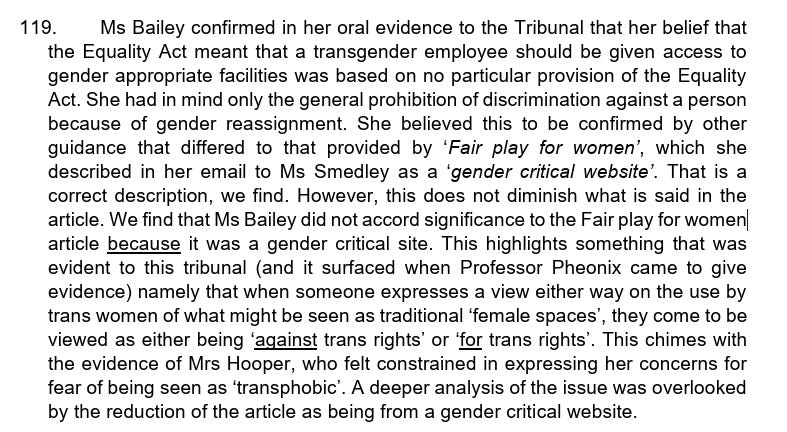

Fast forward nearly precisely two years and the following paragraph appears in an employment tribunal judgment of the Darlington Nurses v County Durham and Darlington NHS:

The idea that anything ‘gender critical’ can or ought to be dismissed because it is gender critical is no longer a viable argument. The bubble has burst. The fact that the judge went on to accept, in its entirety, my evidence of the group disadvantage experienced by women by the presence of a biological male who identifies as a woman is also evidence of the distance we have travelled in two years.

What is clear is that the first flush of cases is over. The newer employment tribunals (like Sandie Peggie’s, like the Darlington Nurses) are no longer about whether gender-critical beliefs are protected. They concern something more substantive: the slow, painful unwinding of the effects of organisational implementation of Stonewall law.

What is most revealing, however, is what has not followed my tribunal.

If legal clarity automatically translated into institutional change, conflict should have diminished. Instead, we continue to see high-profile disputes across healthcare, education, and public services. Nurses disciplined for objecting to mixed-sex changing facilities. Professionals sanctioned for refusing to deny biological reality. Employers defending policies that place women in legally untenable positions. Questionable ethics of puberty blocker drug trials. Prison placement policies.

These cases and conflicts are not anomalies. They are diagnostic.

They show that the problem is no longer legal uncertainty. It is institutional resistance.

One consequence of this resistance has been the increasing reliance on litigation as a means of correction. Women are repeatedly forced into employment tribunals and courts to compel organisations to do what the law already requires. This has produced legal victories — but it has also produced a new and troubling pattern of harm.

In tribunal after tribunal, women are required to disclose deeply personal experiences: workplace bullying, psychological distress, harassment, prior experiences of sexual or physical or emotional abuse at the hands of men. Remote hearings, introduced under the banner of accessibility and so critical important in bringing into the light the ridiculous arguments put forward defending discrimination, have widened exposure of those women’s lives. What was once confined to a courtroom is now observed by audiences far beyond the immediate parties.

Women find themselves narrating the most intimate and often traumatic aspects of their lives to unseen observers — commentators, supporters, critics — subject not only to legal judgment, but moral and political judgment too. Even where outcomes are favourable, the process itself can be punitive if only because privacy is eroded. Dignity is compromised. The costs are unevenly distributed, and they are overwhelmingly borne by women.

This raises a serious question about strategy.

Litigation has been necessary, but it is not sustainable as the primary mechanism for institutional change. It never was and it never will be. Lawfare clarifies rights, but it cannot reform organisational cultures ideologically invested in misinterpreting or resisting the law. Nor should women be required, again and again, to sacrifice privacy and wellbeing to secure compliance with settled legal principles.

The failure of government to issue timely EHRC Code of Practice has made this worse. In the vacuum, organisations invent their own interpretations — often shaped more by reputational anxiety or activist pressure than by law. Some even boast of their refusal to implement sex-based equality. We need our elected government to act and to act now - they need to defend the law.

Meanwhile, misinformation continues to circulate unchecked: from training “experts” who misrepresent the Equality Act, from managers claiming nothing can change until the EHRC acts, from claims that single-sex provision harms transgender people — claims unsupported by evidence and incompatible with law. These assertions function rhetorically, shifting attention away from women’s rights and reframing lawful boundaries as moral failings.

Since January 22, 2024, something else has changed.

The so-called “gender wars” are no longer niche. They are no longer confined to specialist circles. They are now recognised as everyday governance questions.

This mainstreaming matters. Not because it resolves disagreement, but because it reframes the issue. What we are witnessing is not a culture war. It is a systemic failure across institutions to reason clearly, to set boundaries, and to apply the law under pressure.

Seen this way, employment tribunals are not the cause of the conflict; they are its by-product.

My case, and those that followed, reveal something fundamental about this moment: when organisations lose the capacity to distinguish belief from misconduct, law from policy, compassion from coercion, the burden of correction falls on individuals — and disproportionately on women.

That burden cannot remain where it is.

The law is settled. The question now is whether our institutions are willing — or able — to act accordingly.

We have arrived. The question is whether the structures around us are prepared to catch up.

Plus ca change!

Jo this is all so depressing. You were the reason I started the OU Criminology and Psychology course. I assumed, wrongly, that the Supreme Court judgement would make a real difference.

Thank you for continuing the fight. I am now. Volunteering in our local ( male) prison. All of your insights re criminology/power etc so valuable but so angry about all the other stuff!!!