Why case by case risk assessment is not the solution for safeguarding women and girls in custodial settings

First, a little bit of history

The assessment and management of risk as a central pre-occupation of courts, probation, police and prisons is a late 20th century invention. This is not to say that ‘risk’ was not a concern in the administration of criminal justice prior to the late 20th century. Rather it is to stress that the technocratic assessment and management of offenders’ risks as a means of controlling crime is a relatively new approach to crime control. It is rooted in the late 1990s New Labour agenda to modernise government and their drive for ‘evidence-based policy and practice’ and propped up by the logic of actuarialism.

Actuarial justice and evidence-based practice – what is it and what are its problems

Actuarial science is a form of statistical modelling that is used to predict and manage risk in insurance and from its earliest days was used as a means to set insurance premiums. The reasons for why a statistical and mathematical science should end up underpinning contemporary criminal justice practices is an essay for another day, but suffice to say that by the late 1990s New Labour introduced a series of policies aimed at managing ‘the crime problem’ by introducing measures to minimise the ‘risk of offending’ that some people posed. This was an enormous shift in criminal justice practice because individual motivations or the meanings of crime were no longer seen as being at all relevant. Instead, criminal justice practitioners became risk managers whose main skill sets revolved around assessment of risk and planning interventions and programmes with offenders that were tailored, not to improving the local community or understanding the meanings and motives of offending, but around reducing the risk factors that were highlighted in the risk assessments. The ‘risk-need-responsivity’ model of work, pioneered in Canada, became the beloved model of practice for many countries (see https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprobation/research/the-evidence-base-probation/models-and-principles/the-rnr-model/ for a summary of this and as an example of the unquestioning acceptance of this model of justice). In this model, offenders are no longer seen as individuals with unique circumstances and challenges that need addressing. Instead they are processed as a walking set of risk factors. The key criminogenic risks being:

· their history,

· pro-criminal attitudes,

· pro-criminal associates,

· anti-social personality traits,

· school / work,

· family or marital status,

· substance misuse / abuse,

· leisure / recreation.

The list of these risk factors has been developed in conjunction with the expansion of evidence-based practice in which offenders are relentlessly assessed, their assessment scores (yes, risk assessments lead to numerical scores) fed into large databases and efficacious practices of interventions developed from them. Yet there are huge problems with the risk-need-responsivity approach and its evidence base. Most of the criticisms boil down to two issues. Firstly, risk assessment – even including ‘dynamic’ factors (i.e. those aspects of an individual’s situation which is amenable to change) - is a backward facing exercise that fails to account for the role of social inequality and disadvantage and creates ever weakening correlations between ever expanding lists of risk (and protective) factors. Hence, it comes as absolutely no surprise the strongest predictor (apart from sex) of whether someone will offend in the future is previous contact with the criminal justice system. The evidence would suggest that getting into trouble with the law is likely to make you an offender! Second, and more important for this blog, though, is the fact that the list of risk factors has not emerged out of no where. Facts (and factors) do not speak for themselves. They are created by people, academics, practitioners and being so reflect how they see the world. I suspect that when determining that a pro-criminal attitude was one risk factor the researchers were not thinking about the unlawful or sharp business practices of tax avoidance and evasion. I suspect they were not thinking about individuals’ willing to unlawfully infringe others freedom of speech in debates about the relative importance of gender identity and sex in criminal justice. And, as far as I know, there is no risk assessment that includes misogynistic attitudes as part of someone being ‘pro-criminal’ – and yet this strikes me as a major risk factor for a man likely to be violent to a woman or girl. Likewise, that a person is not in employment, training or education seems a bit of a chicken and egg problem – perhaps being permanently excluded from a school hellbent on ensuring its targets for performance might propel some young people into a way of living that is conducive to less than law-abiding behaviour. You get the point.

Having started my career at the beginning of actuarial justice, I think its single largest achievement is the obfuscation of matters of crime and justice with technocratic language of risk assessment and the massive databases that now exist - repeating time and again and confirming time and again that those who are most ‘at risk’ of offending are precisely those who score highly in the domains assessed above. What a surprise. Afterall, the risk factors were extracted from the backgrounds of people in the criminal justice system.

What does this have to do with transgender prisoner placement and the problem of risk assessments.

Everything.

Risk assessment is only one component of actuarial justice and only one part of a strategy for crime management. The ‘tools’ take the shape of a series of questions or a template that guides practitioners in their thinking. They have been designed for a specific purpose – to tailor the programme that an individual offender needs in order that their risks are reduced. Individuals are risk assessed so that practitioners can figure out what ought to be done for them in light of an evidence base about efficiacy (effectiveness) of specified courses, treatments and so on. Or, in the language of youth justice, evidence-based practice is all about assessment, planning, intervention and supervision.

What risk assessment was never meant to do was be a tool by which safeguarding could be achieved. Youth justice practitioners would not use an ASSET assessment to figure out whether a younger family member needed safeguarding from a sexually harmful teenage brother. All assessment tools are there to identify the risk factor in order to address them in the individual. That anyone proposes that the same tool that is used to assess the risk of sexual reoffending can also double up as a method by which safeguarding of women in prison can be achieved is, on one level, a specious argument.

But let’s dig a little deeper.

Ministry of Justice have recently adopted the use of the OAsys Sexual Reoffending Predictor (OSP) tool to assess the risk of sexual reoffending of all those who are serving a sentence for a sexual offence. OSP is a set of questions, the answers to which generate a score that indicate whether the individual is high, medium or low risk of sexual reoffending. It is a ‘validated tool’ in that its predictive capacity has been tested. Predictive capacity is expressed in terms of a ‘C Index’ with the 1 representing a perfectly predicting tool (i.e. everyone assessed according to the tool will act as the tool suggests and either go on to commit more sexual offences or not). OSP has a C Index of around .7 suggesting that it has some predictive capacity.

But, there are two important caveats.

The Ministry of Justice states that:

There is no actuarial risk assessment tool available for women. OSP is not designed to be used in the assessment of women convicted of sexual offences. It must therefore not be calculated or used with anyone recorded as female. (Taken from OAsys Sexual Reoffending Predictor)

There is a very good reason for this. Too few women commit sexual offences for any risk assessment tool to be developed, validated and implemented. Remember: risk assessment ‘tools’ require large databases to be developed. Hence, all sexual offending tools are developed in relation to the one demographic who are staggeringly overrepresented in those convicted of sexual offences – men. 98% of sexual offences are committed by men.

The Ministry of Justice also state:

As per ‘The Care and Management of Individuals who are Transgender’ policy framework, staff should always record legal gender on any official systems. When the assessor records … that the individual is male, this automatically triggers OSP scores to be calculated and displayed. This means that OSP scores will be displayed for a transgender woman without a Gender Recognition Certificate, as they will be recorded as legally male within the assessment. There is currently insufficient evidence on the predictive accuracy of OSP scores in these circumstances, so assessors should treat the scores with caution in these cases, considering the scores within the context of the circumstances of the individual and the pattern of offending. (italics added, taken from Operational Guidance)

Translated this means the following: the number of males in the criminal justice system who also identify as transgender or as women is very low relative to the total male population. Those who are convicted of a sexual offence are an even smaller subset of the already small overall (known) offender transgender population. With low numbers comes an insufficient dataset from which to make reliable risk calculations. So the instruction given by Ministry of Justice to practitioners is not to trust the score.

How then are transgender prisoners ‘risk assessed’ and how do the professionals who are tasked with making the decision about prison placement make that decision?

The Care and Management of Transgender Prisoners: Operational Guidance (2020) developed by HMPPS Diversity and Inclusion Team provides the Complex Case Boards (the committee of professionals from the prison service, probation and so on who make the decision about transferring prisoners) with errm ‘helpful’ guidance. It states:

“A proper assessment of risk is paramount for the management of all individuals subject to custodial and community sentences. The management of individuals who are transgender, particularly in custodial and AP settings, must seek to protect both the welfare and rights of the individual, and the welfare and rights of others in custody around them. These two considerations must be considered fully and balanced against each other.”

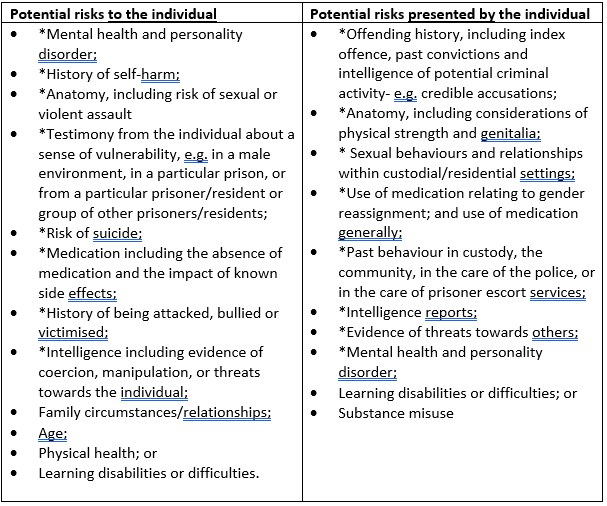

Yet, as pointed out above, there are no validated risk assessment tools for transgender offenders. And so the guidance for complex case board is to “consider” the following – the asterisk indicates “critical factors”:

What does not appear on this list of considerations is:

risks posed to the dignity, privacy and well-being of a captive population of women who have a disproportionately high level of trauma;

any guidance as to what is considered an acceptable level of risk that women prisoners in a female prison must endure;

how the considerations ought to be ‘scored’ or ranked.

Or most importantly, when risks have to be balanced, how to resolve the inevitable contradictions and conflicts that are created. Do the requirements (and *rights*) of women of faith to be incarcerated in single sex spaces matter more than the *rights* of an individual transgender male prisoner? What about the right (and arguably need) of a female prisoner to single sex rehabilitative programmes that address male sexual violence? Does her rehabilitative need matter more or less than the need of a transgender prisoner to be in the company of women? For me, the missing guidance speaks volumes and leaves the Complex Case Board dabbling in details that, quite frankly, utterly miss the point. As to whether the list of considerations the Complex Case Board address is capable of ensuring safeguarding, well…. Let’s just say I have my doubts. To this, the Ministry of Justice and other supporters of mixed sex prisons might argue: (leaving aside Karen White) there is no evidence of harm. Yet, as someone on twitter pointed out to me only a few weeks back – “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence”. There has been no systematic or independent research of the effect of mixed sex prisons on female prisoners in England and Wales. None.

A final thought:

The cobbled-together patchwork of lists of considerations and the fudging of assessment seems at best a cavalier approach by the Ministry of Justice to what is a safeguarding issue. I suspect it also flies in the face of our established principles for how we protect and safeguard adults. Whilst the public and political rhetoric dresses up the approach in the high-falutin’ technocratic language of actuarial justice, in practice the entire approach relies on the discretionary judgment of the Complex Case Boards. To date, there is no evidence about how efficacious this judgment is, or indeed the actual or tacit knowledge required by board members to make these decisions. To my knowledge, there is no professional training that board members are given and it is not clear at all what guidance board members are given on exactly how and in what way the two lists of considerations are to be balanced against each other.

So, do I have faith in a risk-assessed case-by-case approach? Absolutely not. Any attempt to argue that what we currently do is capable of keeping women safe is utterly spurious. And don’t even get me started on why women’s rights to single sex space ought to be balanced rather than maintained, ensured and protected.

Jo, I’d like to share this with my sister-in-law, Rona Epstein. It’s that okay with you. I think she may want to subscribe to this Substack. It’s very interesting to see it laid out like that. I, for one, knew nothing about how risk assessment was done.

Thank you for this. As a criminal defence solicitor grappling daily with risk assessments, which I consider to be crude at best, there is nothing new to me in this but it is very helpful to see it so clearly set out. One additional factor that appears to have been recently added (informally or formally?) to the list assessing risk of reoffending or of harm is experience of trauma.